Meet the author and the lead character, two for the price of one.

Yep, that’s me, warming my toes in the den of the kitchen, an INFP pacifist who feared my emotions, keeping them locked in the image of the old nailed-shut door in my father’s shop basement.

The me in the story is the me in real life, minus the dramatics of the novel. The world of the 60s in a small midwestern city is unrepeatable now. It was a world on the border of two eras. In a way, so was I. While the cultural revolution was brewing on the coasts, it trickled slowly into the Midwest. My world was still filled with neighborhood grocery stores and bike rides through old tree-shaded streets filled with fading memories of summers when everyone spent the evening on the front porches and promenading on the walks to see and be seen by the neighbors. The older folks still sat out there, but there was no one to talk to anymore.

Schools had yet to consolidate. There were no school busses, at least on the elementary side of things, just lots of little local schools filled with a mix of newer progressive teachers and older “spare the rod” McGuffey Reader holdovers.

It was homogeneous where I grew up. Every kid had pretty much the same ethnic heritage and the same backstory. We were all turned loose to fend for ourselves when we were not at school. Hence, socialization was left up to the kids to figure out themselves. I played with random neighbor kids fine, but as I grew, I came to realize I was not like the other kids at all.

So, I spent much of my childhood with imaginary friends and reacted oddly to seeing the history of my hometown around me. The visions I experienced were common, and I did spend time in cemeteries talking to the headstones, asking questions about who they were and what their lives were like. My mother says I would cry when passing collapsing old barns and farmhouses while taking drives through the country, another long gone form of entertainment. The incident with the Kool-Aid really happened, as did the mysterious crack on the head on the stairway of the old department store. I really did walk down the abandoned streets of long-vanished shops and try to see them in their heyday. Other kids found me weird and had little tolerance for me.

The story arc of the novel forces John into the impossible situation of committing a violent act to break the loop of tragedy and results in the complete breakdown of his mental image. Again, in real life, I was conflicted by wanting to lash out at the bullying I received from both adults and kids and my soul’s desire for peace. Sometimes, when pushed too far, I lost all sense of restraint and would injure whoever was taunting me. It made me clamp down on my emotions in fear of where they would lead me. If I had been pushed just that little more, the results of my life would have been closer to the fictional version. I was fortunate to be rescued by my mother, who managed to get me one of only ten slots in the entire city for a “Learning Disabilities Class.” Where it didn’t stop every problem, my teacher gave me the tools to understand them. As an adult, I live with one foot in either realm, so the door is left open as to whether the events in my life are real or just my delusion. Looking back on memories, the distinction becomes less relevant. It is the ark of one’s life that remains and what you have learned from living it.

I am now the old, wandering, crazy author of the epilogue. I carry my ghosts with me, and they have taught me much. I love them all. The world of my childhood may be gone, but the echoes are still in my head. Their voices became this story.

Is Edward real? Confessions of a madman.

Edward was my imaginary friend as a child, who faded away as I grew. Several years ago, after the death of my wife, I realized I had to find out who I was all over again, so I cast back to my childhood and found him still there in my memory.

Edward was always from the past; even then, I saw him in the window of the big estate house one block over and down every time I would pass it. I would wave, and he would wave back, without fail, no matter what time of day or season of the year. Part of me knew he wasn’t real, but I wanted him to be, so he was always there. He would come see me on the sidewalk in front of the house and I knew I had a friend.

I remembered sharing my fears and frustrations with him before and found I could return to that space again. From my adult perspective, I questioned just how much my mind could fill in when I pictured him, and how I could know so much about a world I was born too late to experience. As a child, I would just accept it. So when I indulged in the same willing suspension of disbelief as my adult self, Edward became perhaps more real to me now than he did then, and with that, questions took shape.

What exactly is reality? What are ghosts? Could Edward, in fact, be real? Could we be friends from two different spots on a timeline? Is time really linear at all? What would it mean to me if I accepted him as real now? It was a concept that, once I broke that barrier, changed everything.

I knew him, perhaps another side of my own personality, but maybe not. We share some tendencies, but Edward is more outgoing than me, intelligent, loves to quote Aristotle, and has been educated in a British boarding school. He suffers from emotional dysregulation and will spiral out of control in emotional situations, while I just denied mine. He is introspective; I am impulsive. We are more like counterbalances for each other. When my story became entwined with his, it became a fuzzy line between truth and fiction.

I believe that the direction/angle at which we view reality alters our perception/understanding of it and of our true nature as sentient souls, hence both Kierkegaard’s observation and John continually repeating the message, “Time is not what you think it is.” This came from the mathematical construct of “Imaginary Time.” Stephen Hawking posed that using this mathematical model raises fundamental questions on the nature of reality, as to what is real and what is imaginary, which are only the distinctions in our minds.

Admittedly, I have stretched the concept like a cheap sweater, but my genuine observations as a child of things before my time could be explained both as an overactive imagination and as a time-shifted experience. As the late great Mr. Hawking hinted, is there a real distinction? The entire “time bubble” aspect of these two stories was always shadowed by the distinct possibility that both characters, John and Edward, could co-exist in their respective lives because they were both imaginary friends to each other but real within their own dimensional space.

His St. Joseph is the one I only heard stories of, the remains of which I wandered through as a child, straining to understand. Like the 60s, it was another transitioning period. In 1914, his gentile “Golden Age” was fading fast, and although the city was still thriving, the shipping hub had migrated 50 miles south to Kansas City, taking more and more manufacturing businesses with it. The old ones stayed out of convenience, but progress and consolidation would leave many of them irrelevant in the coming age.

Edward was fading too and taking that age with him. When he was gone, there would be no one left who remembered sitting in the Tootle Opera house or hopping the overhead electric trolly with a passel of orphan boys on an autumn evening. I had this conversation with my grandmother years ago before she passed, and soaked up the remembrances, even though they were pale copies of the original. Now, it was only Edward, still young and full of the excitement of childhood experience. It hurt me to think he would vanish forever.

So when my story became a novella, Edward played a big part, but after I published it, I found him, begging me to tell the rest of his story too. I did not know where to go with it, but he did. It felt like taking dictation, and when it was done, I was an emotional mess. I cried as I typed and felt every memory as we went. It was his gift to me, the last friend of my inner child. He led me through the most cathartic experience of my life and neatly explained everything in my childhood that I never had answers to before. He had come back to save me from the dark hole I was in.

So, to answer the question for all time, “Was Edward real?” I can honestly ask, as the author asks back, “Is he real to you? If he is, then yes.” I know he is part of my soul, my first and always best friend.

David, Harry Langdon & Vaudeville

David is such a pivotal character in Edward’s and eventually even John’s life by the end of the story. His fate was necessary to the story arc, but I felt so guilty that I resurrected him under the name Lincoln and gave him his own musical!

Theater kids get a bad rap, but often, they are introverts who find hiding behind the mask of a character the only way they can face the world. When I realized David was using the stage as his window game, it opened up a whole extra dimension for his life.

David’s arc of unfulfilled potential, tragedy, triumph, and ultimately, a shining star in the memory of the very few he touched gave him a tremendous impact that reverberated through several generations. It may lean towards melodrama, but that would be David all over.

When I began writing the character of David, his death scene lacked any emotional punch because he had no real backstory other than a friend. As I pondered that one, a video popped up on my Facebook feed of a song that had been featured on a popular sitcom I had watched regularly with my late wife, and this had been the last episode we saw before her death. We both commented on how well the young man sang at the time, so I took it as a sign and looked him up. At his young age, he had an impressive resume. There were numerous videos, interviews, and recorded live streams of him. His exuberance, big smile, and beautiful voice became the basis for the character that David needed to be, so now his loss had a genuine impact and proved to be a reoccurring and emotional anchor for Edward clear to the end.

The Crystal Theatre was a 400-seat vaudeville/movie house built in 1907. It was about two blocks from my father’s shop and was one of dozens of such theaters in downtown St. Joseph at that time. It ceased operation in 1938 and was demolished in 1950, well before my time, but my mother remembered seeing movies there as a child. Until writing the ending, I had no idea that the site is now a parking lot used by Highland Dairy, the company that bought out Western Dairy, where Edward worked as a young man. Having him make that emotional connection, in the end, was me making that connection in real-time. I also discovered that my sister’s best friend, who accompanied me around while in my sister’s care back in the ’60s, was part of the family that owned the dairy. More connections.

I stumbled on the song ‘No Man’s Land,’ which had been a hit for Al Jolson in 1918, and I considered that another fortuitous circumstance. Having David sing it made it seem like it should be there as a message after having already called the stables in later chapters.

There were so many acts that defined the early days of radio, television, and movies that originated on the vaudeville stage, and many of those started as kids, like David. Vaudeville was the YouTube of its day, where almost anyone could get on a stage and try something new. It bred the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Sammy Davis Jr., Bob Hope, Fred Astaire, May West, and others. The show’s opening act was usually a “Silent Act,” whose job it was to warm up the still noisy audiance so they would settle down for the rest of the show. The masters of this art form, like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin, were the perfect fit for the medium of silent movies that eventually took vaudeville place.

Harry Langdon (June 15, 1884 – December 22, 1944) was another person who came from Council Bluffs, IA and went on to be considered one of the big four in early silent pictures. His early films were directed by Frank Capra, who was new to the movie business and very much the style of others of the time. Langdon had an inciteful philosophy on comedy, stating, “Comedy is a satire of tragedy…deliciously comic moments, on the outside, are full of sad significance for those who realize the sinister characterization of the situation. “At the time of our story, he was playing the smaller Midwestern vaudeville circuit. I found an itinerary listing him in St. Joseph at the Crystal Theater, making him the perfect act for David to share the stage with.

His movies were quite funny, and having Edward see one several years later was both poignant and telling, seeing Harry’s prediction of the end of Vaudeville echo in his memory of his and David’s backstage encounter with him.

The cast of guest appearances. Other real people in the tale.

Lizzie King was a holdover from the real wild wild west days, and by Edwards time, already infamous. My father told a story of walking down the street as a child with some friends on a hot summer day, when an old lady invited them up on the porch for lemonade. They obliged and afterwards, thanked her. She replied to be sure and come back when they were older. Only later did he find out that she was a notorious madam and the had been sitting on the porch of her brothel.

Whatever her motivation, she presented a soft front for those kids, and that story begat the coco scene with Richard.

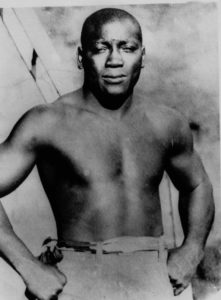

Not from St Joseph, but passing through, was Jack Johnson, (March 31, 1878 – June 10, 1946) who apparently wanted to be in the story himself, and rightly so. The story’s timeline put him, a free man, at last, 28 miles away on the very day that Edward and Richard had their confrontation. It would be entirely plausible that he would have overnighted in South St. Joseph, home to the black population of the city, on his way back east after being released from Leavenworth.

Nicknamed the “Galveston Giant”, he, at the height of the Jim Crow era, became the first African-American world heavyweight boxing champion (1908–1915). Widely regarded as one of the most influential boxers of all time, his 1910 fight against James J. Jeffries was dubbed the “fight of the century.” According to filmmaker Ken Burns, who produced a two-part documentary about Johnson’s life, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, “for more than thirteen years, Jack Johnson was the most famous and the most notorious African-American on Earth”. Transcending boxing, he became part of the culture and history of racism in the United States.

In 1912, Johnson opened a successful and luxurious “black and tan” (desegregated) restaurant and nightclub, which in part was run by his wife, a white woman. The government used that against him, and Johnson was arrested on charges of violating the Mann Act—forbidding one to transport a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes”—a racially motivated charge that embroiled him in controversy for his relationships, including marriages, with white women. Sentenced to a year in prison, Johnson fled the country and fought boxing matches abroad for seven years until 1920, when he served his sentence at the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth.

On June 10, 1946, Johnson was killed in a car crash near Franklinton, North Carolina, after driving angrily away from a segregated diner that had refused to serve him. He was 68 years old. Johnson was buried next to his first wife, Etta Duryea Johnson, who died of suicide in 1912 at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

His whole story, the subject of numerous books, is too long to put here but do look it up. He is not well known to younger generations now, but he should be. He was one of the most influential African Americans of the 20th century, becoming the first black heavyweight boxing champion, sparking race riots across the country and the caucasian community’s search for the ‘Great White Hope’ to take down who they saw as an impudent black man. He served as an inspiration for the black populace, and I am proud that he chose to step in and save my characters.

Ezock Spair, AKA Murphy (1898-1988), was real, one of three brothers. The story, as I heard it, was that Jess Jutten, a fire captain, gave Ezock the nickname. As a young boy, Ezoch hung around the fire station on St. Joseph Avenue and was frequently in fights. “You fight so much you should be Irish,” Jutten told him. I’m going to call you Murphy.” The nickname stuck.

For years, he was a paperboy selling on his corner, and everyone knew him. As he got older, he and his brothers branched off into selling novelties at the town parades and auditorium events. In the winter, they set up a stall in an alleyway next to the dime store and sold mistletoe for a holiday they didn’t celebrate.

He was always smiling when I saw him, always ready for the next opportunity, and always kind to me. He died a local legend, and It pleased me that he could bridge the gap between the two timelines of this story.

No Man's Land, Louis Hine, and child labor

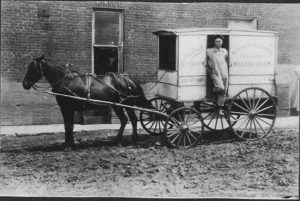

Delivering milk in trucks means they can all leave from a central depot. Horses are a different beast, pardon the pun. Sending a horse and wagon clear across town and then out on rounds was too much for the horse, so often, dairies in cities would deliver the milk by one wagon to a distribution stable where it would be dispersed via a local team. I don’t know if Western Dairy used this method, but it would make sense. South St. Jo was considered another town back then and quite a ways from the main dairy.

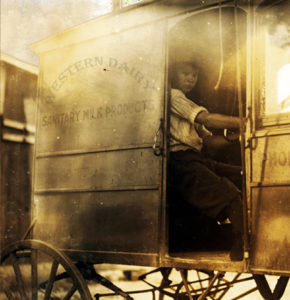

Western Dairy was one of the oldest dairies in St Joseph

Hannafin & Fenner were partners in the beginning

George and Augie Fenner and numerous other members of the Fenner family owned and operated it for many years. It was bought out twice, and Highland Dairy in Iowa ceased retail home delivery in the late 1970s, eventually tearing down all the St. Joseph structures. All products are now trucked in from Iowa.

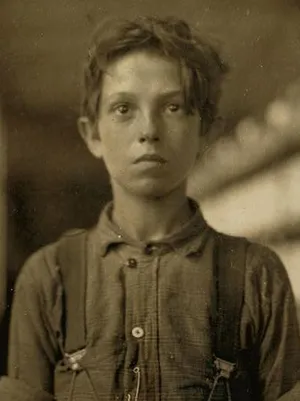

When the U.S. joined WWI, it left a labor vacuum that, thanks to the absence of child labor laws, was filled with workers who were too young to fight. Milk delivery was one such job that could be done using children. The boy seated in the wagon on the book cover was taken by Lewis W. Hine on August 18, 1916, in Bowling Green, Kentucky, with Hine’s description as:

“Edgar Kitchen is 13 years old and gets $3.25 a week working for the Bingham Bros. Dairy. He drives a dairy wagon from 7 A.M. to noon seven days a week. He works on a farm in the afternoon (10 hours a day) seven days a week—a half-day on Saturday. He thinks he will work steadily this year and not go to school.”

His wages would be equivalent to $63.00 a week in 2024 dollars. In 1917, a basic adult laborer, floor sweeper, etc., could expect to make at least $312.00 a week in 2024, for the same job, showing why child labor was so attractive for business.

Lewis Hine’s photographs for the National Child Labor Committee, now considered some of the most famous and influential in American journalistic history, were vital in ending child labor in the United States. He began photographing these children in 1908 when the cruel reality of child labor was carefully hidden behind factory walls. He would introduce himself as a fire inspector, insurance representative, postcard vendor, or industrial photographer to get his camera into these secret places. Exposing these images to the public brought him death threats and physical violence, but his passion for ending these children’s plight and his desire to see them get a proper education became his life’s goal. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 finally began to dismantle child labor practices in the U.S., but Hine found little work after that and eventually lost his house and was forced to apply for welfare. He died on November 3, 1940, at 66 years of age.

The orphans

The boys themselves were meant to be passing players in the story, but Edward had other ideas. As he had been thrust into the role of an orphan, it became apparent that finding a family amongst them would be the story’s theme. That meant I had to make it as accurate as possible and take an honest look at real children who have undergone abuse, neglect, and sometimes extreme trauma.

There are an average of 400,000 children in foster care in the US at any given time, and around 120,000 need adoption. Most of them are above the age of 7. There are too few homes willing to care for them, so many age out at 18 with no families and few resources to survive. Many end up homeless, in prisons, or dead. This is nothing new and was just as true in 1914 as in 2021. These were the children of No Man’s Land. They still are.

These kids are seldom dealt with in fiction in an honest manner. They are not psycho killers or, on the other extreme, poor Dickensian waifs whose lives are suddenly all better when the benefactor sweeps in. They are often like young soldiers returning from battle, spending the rest of their lives trying to learn how to deal with often horrible or at least disrupted childhoods. Post-traumatic stress is a common diagnosis for them, and while many learn to deal with it, it sometimes takes years of hard work for them to find peace.

Richard:

Richard’s character caught me by complete surprise. I had no intention of making him a main character, so I couldn’t understand his reaction when he met Edward. I left him upstairs on the bed for three days, completely stumped. Then I saw one particular child’s face, with his steel-gray eyes and an impish smile, that Richard’s character suddenly formed in the space of a few seconds. When I started writing again, and as Richard confessed his tale, I almost fell out of my chair. Suddenly, the entire story made sense. Richard was the lynchpin for everything in Edward’s life, including his uncle. Now, so much of what I had Victor say in the book’s first half flowed into this, revealing family secrets and leading to the redemption of this mad, troubled man we knew little about.

Albert:

Italian by descent, Albert, the oldest of our group, now in his mid-teens, is reminiscent of the “aged out” foster community. No longer a child, they have no support from any family and are left to face the world on their own. Albert is laid back, observant, and fair. He’s also intelligent and has learned to look out for himself and have the empathy to see the pain in others around him. He is like so many amazingly astute and deep souls who have used their pain to help other shattered children put their lives back together. They bring hope in the midst of so much darkness. He is also business-oriented, and his entrepreneurial tendencies were less about profit and more about keeping his chosen family together and safe.

Then, there is Harold. He is an amalgamation of many amazing souls who were born with FASD, or Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Alcohol does way more damage to developing brains than drugs. Much of it is done before the mothers even know they are pregnant. There is no cure because it is physical brain damage. You may sometimes meet people who are in this spectrum and never know it. They are often intelligent, witty, and happy people and can also be physically beautiful. What you can’t see is an underdeveloped corpus callosum, frontal lobe, or other affected areas of their brain. It affects up to 5 percent of Americans and can leave them with poor decision-making, a lack of understanding of cause and effect, difficulty planning, impulsivity, and distractibility. They often have trouble performing tasks in a sequence. Their speech can be slow and halting because they have to think about everything they say carefully and frequently with effort.

Because of these inabilities in their thinking, they are often interpreted as lazy, belligerent, disrespectful, and immoral through no fault of their own. They often end up in situations that involve the law yet have little ability to deal with the police, attorneys, judges, social workers, psychiatrists, corrections and probation officers, etc. Often, police, courts, jails, and prisons don’t recognize them either, and they are punished for things that they are unable to understand.

I think that portraying Harold’s whole life—from being used as a small child to the simple tasks, repetition, and loving support given to him by his adoptive brother—made him the heart of his community. There are a lot of real-life Harolds out there. Many are in trouble and deserve the kindness that Albert so freely gave. If you find one in your life, just understanding them will provide them with so much.

Three Mothers.

Lorraine Hanson

Edward’s adoptive mother was loosely based on Mary Whiton Calkins, the American philosopher and psychologist whose work informed theory and research of memory, dreams, and the self. One can imagine the conversation she and her husband must have had about Edward and then, later, the evolving story of Richard. Blessed with a fine analytical mind, she nonetheless tempered that with parental love. She was respected as a professional in a field young enough to have few expectations, unlike genteel Elisabeth. Giving Edward two significant influences to balance between gives him a unique perspective that shapes his troubled character.

Elisabeth Powell

Edward’s birth mother isn’t based on anyone in particular but is a woman of her time.

As the ward of a wealthy family, Elisabeth would be given a classical education, and emphasis would be given to upper-class values of presentation, elocution, and adherence to social norms. Even amidst a marriage based on an illusion, keeping up appearances left her with no genuine power to change it. Placing all her hopes on her only surviving son instead while her secret life was crumbling beneath her, she was left torn between scandal, which would destroy Edward’s already perilous future, or ending her own misery and, in doing so, freeing her child from the curse she believed she brought on them all.

John’s Mother, Georgie Goldsberry

John has his family around him, but his real mother played a big role in helping him deal with this problems.

She stood up the the school board, and eventually secured a spot for him in St. Josephs first “Learning opportunities” class, which John says saved his life.

She went back to collage as to study psychology, so she, amongst other things, could help John through his childhood.

She herself was a highly regarded executive assistant, first to a college president, then to a the president of a major theme park, where she helped bring together Dollywood in Tennessee.

The Bright Young Things & West End Theatre

The novel opens with a vision John sees from the perspective of sitting in a boat in the Thames. His companions are unknown to him, but eventually play a pivotal role in Edwards story.

Coined by the press, the ‘Bright Young Things’ were the younger sons and daughters of the aristocracy and socialites seeking to advance their careers through association in 1920s London. They were obsessed with jazz, threw flamboyant fancy dress parties, and went on elaborate treasure hunts through nighttime London. Some drank heavily, used hashish, cocaine, and heroin, and indulged in anything shocking to the staid society of their elders, thereby starting the modern cult of celebrity. The paparazzi were fascinated by their outrageous behavior.

They developed their own slang, using words such as ‘darling,’ ‘divine,’ and ‘bogus.’ Cross-gender behavior and same-sex relationships were welcomed by the group, although against the law in Britain in the 1920s.

When the stock market crash of the latter 20s left many poor and unemployed, their lavish lifestyle was suddenly viewed as vulgar by the masses, and its members became symbols of everything that was wrong with aristocratic society.

Somewhat on the periphery were many in the West End /Theater scene of the late 20s and early 30s, including British playwright and actor Noel Coward and American Actress at large Tallulah Bankhead, both of which were known for pushing the envelope to the breaking point. That our band of miscreants would seek shelter with them would be totally within character. They meet backstage at the Globe Theatre, London (now called the Gielgud Theatre) after a performance of Fallen Angels, a comedy by Coward. The central theme of two wives who slowly get drunk onstage and plot adultery met hostility from the office of the official theatre censor, who said the loose morals of the two main female characters “would cause too great a scandal.” It was only allowed to be performed after the personal intervention of the Lord Chamberlain.

Stephen Tennant

21 April 1906 – 28 February 1987

Tennant was born into British nobility, the youngest son of Edward Tennant, 1st Baron Glenconner, and Pamela Wyndham, one of the Wyndham sisters whom John Singer Sargent painted. His mother was also a cousin of Lord Alfred Douglas (1870–1945), Oscar Wilde’s lover. On his father’s death, Tennant’s mother married Lord Grey. Tennant’s eldest brother Edward – “Bim” – was killed in WWI. His elder brother and fellow BYT, David Tennant founded the Gargoyle Club in Soho.

During the 1920s, Tennant was known as the brightest of the “Bright Young Things”, and was the model for Cedric Hampton in Nancy Mitford’s novel Love in a Cold Climate, and Lord Sebastian Flyte in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited.

During the 1920s and 1930s Tennant had a sexual relationship with the poet Siegfried Sassoon. It lasted some six years before Tennant put an end to it. Tennant died in 1987, having outlived most of his contemporaries.

Siegfried Sassoon

( September 8 1886 – September 1 1967

Siegfried Sassoon, named by his mother because of her love of Wagner’s operas, was born to a Jewish father and an Anglo-Catholic mother, and grew up in the neo-gothic mansion named “Weirleigh” in Matfield, Kent. Siegfried’s mother was Theresa Thornycroft, from a family of sculptors responsible for many of the best-known statues in London.

Siegfried was decorated for bravery on the Western Front, and became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches and lampooned the patriotic pretensions of those who fueled it. Sassoon quickly became a focal point for dissent within the armed forces when he made a lone protest against the continuation of the war in his “Soldier’s Declaration” of 1917, after which he was given the choice of imprisonment or admission to a military psychiatric hospital. Sassoon turned his life into the fictionized “Sherston trilogy”.

In 1927, Sassoon and Stephen Tennant fell passionately in love, beginning a relationship which would last nearly six years, however, in May 1933 Tennant, then receiving treatment at a tuberculosis sanatorium, abruptly broke off their relationship, informing Sassoon via a letter written by his doctor that he never wanted to see him again. Sassoon was devastated.

Sassoon was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1951, and died from stomach cancer on 1 September 1967, one week before his 81st birthday. On 11 November 1985, Sassoon was among sixteen WWI poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner. The inscription on the stone was written by friend and fellow War poet Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

Brian Howard

13 March 1905 – 15 January 1958

Possibly the saddest real person in the novel, Brian Howard ironically is the one who saw in Edward the broken soul looking for redemption as a reflection of his own. A descendant of Benjamin Franklin, Brian was born to Jewish American parents in Surrey and brought up in London. Educated at Eton College, where he was one of the Eton Arts Society founders, he then entered Christ Church, Oxford in 1923. He was prominent in the group later known as the Oxford Wits. He was part of the Hypocrites’ Club, which included Evelyn Waugh, who would go on to rather cruelly use Brian as the model for Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited.

H was a published poet under the pseudonyms “Jasper Proude” and “Charles Orange,” in A. R. Orage’s The New Age, and the Sitwell Wheels anthology by Edith Sitwell who admired and promoted him in the late 1920s. His verse also was in Oxford Poetry 1924. He became famous for always showing up as a different character at social events, and casual encounters.

In 1929 he was famously involved in the “Bruno Hat” hoax, a spoof London art exhibition by an apparently unknown German painter Bruno Hat (impersonated by the German-speaking Tom Mitford, brother of Nancy and Diana Mitford, briefly mentioned in the novel. Bruno Hat’s paintings were the work of Brian Howard. Howard is also credited with coining the phrase, “Anybody over the age of 30 seen in a bus has been a failure in life”, often wrongly attributed to Margaret Thatcher.

Howard took part in the Dunkirk evacuation in 1939 and assisted in the release of anti-nazi Germans imprisoned in France. He was recruited by MI5 in 1940. Howard had been bullied at Eton for his Jewishness, and this granted deeper insights into the nazis’ national ideology than many journalists of his time. He wrote a series of sophisticated anti-nazi propaganda scripts for BBC radio, some of the earliest to broadcast the facts of the genocidal “eugenics programme” of the Third Reich. Howard’s compassion and fury were evident when, in his radio documentary, he had the anguished voice of one of the Hitler youth leaders’ victims, a small child, cry out: “I am dead. A state doctor killed me in a little shed. It was called the Hitler Room. I don’t think he can know about it. Do you, Herr State Youth Leader?” But, because of his personal behavior, he was dismissed from the War Office in June 1942.

After the war, Howard drifted around Europe, writing occasional articles for the New Statesman, the BBC, and others, but doing no substantial work again. In January 1958, his lover Sam died of asphyxiation from a faulty gas heater. Howard, blaming himself for this accident, committed suicide with an overdose of sedatives. They were buried alongside each other at the Russian Orthodox Cemetery in Nice.

Noel Coward

16 December 1899 – 26 March 1973

Born in 1899 in a suburb of London, Noel appeared in amateur concerts by the age of seven, and had his first professional engagement was in January 1911 as Prince Mussel in the children’s play The Goldfish. He said of his audition “I was a talented boy, God knows, and, when washed and smarmed down a bit, passably attractive. There appeared to be no earthly reason why Miss Lila Field shouldn’t jump at me, and we both believed that she would be a fool indeed to miss such a magnificent opportunity.”

Coward left his lasting mark as a playwright, beginning in his teens, and published more than 50 plays like Hay Fever, Private Lives, Design for Living, Present Laughter, and Blithe Spirit. He also composed hundreds of songs, over a dozen musical theatre works , screenplays, poetry, several volumes of short stories, the novel Pomp and Circumstance, and a three-volume autobiography. Coward’s stage and film acting and directing career spanned six decades.

Coward was homosexual but never publicly mentioned it. Coward firmly believed his private business was not for public discussion, refusing to acknowledge his sexual orientation publicly, wryly observing, “There are still a few old ladies in Worthing who don’t know.” He did maintain close friendships with many women, including the actress and author Esmé Wynne-Tyson, his secretary and close confidante Lorn Loraine, the actresses Gertrude Lawrence, Judy Campbell, and Marlene Dietrich.

He was a trend setter. Sometimes his own success came as a bit of an annoyance.”Why?” asked Coward, “am I always expected to wear a dressing-gown, smoke cigarettes in a long holder and say ‘Darling, how wonderful? I took to wearing coloured turtlenecked jerseys, actually more for comfort than for effect, and during the ensuing months I noticed more and more of our seedier West-End chorus boys parading about London in them.”

Coward was generous and kind to those who fell on hard times. He was known to relieve the needs or pay the debts of old theatrical acquaintances. From 1934 until 1956, Coward was the president of the Actors Orphanage, where he befriended the young Peter Collinson, who was in the care of the orphanage. He became Collinson’s godfather, and this helped him get started in show business. When Collinson was a successful director, he invited Coward to play a role in The Italian Job.

Coward died on 26 March 1973 at his home in Jamaica. A memorial service was held in St Martin-in-the-Fields in London where John Betjeman wrote and delivered a poem in Coward’s honor, John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier read the verse, and Yehudi Menuhin played Bach. In 1984, a memorial stone was unveiled by the Queen Mother in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey. Thanks by Coward’s partner, Graham Payn, for attending, the Queen Mother replied, “I came because he was my friend.”

Tallulah Bankhead

January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968

Tallulah was born into a prominent Alabama political family. Both her grandfather and her uncle served as U.S. senators; her father served as a U.S. representative in Congress and Speaker of the House of Representatives. Tallulah Bankhead’s support of liberal causes were in opposition her own family publicly.

Although her real love was the stage, she made several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat in 1944. She also did radio and television, including appearances on everything from Lucy to Batman.

Bankhead claimed to enjoy drugs, drink a bottle of bourbon, and smoke 120 cigarettes every day. She also openly had a series of relationships with both men and women, including artist Rex Whistler, offering him “an uncomplicated crash course in sex,” Once, Bankhead’s friend called at her from the hallway outside the suite at her hotel, only to be informed by her maid that “Miss Bankhead is in the bath with Mr Whistler.” Hearing her friend’s voice down the hall, Bankhead reportedly shouted, “I’m just trying to show Rex I’m definitely a blonde!”

She was also linked romantically with Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Hattie McDaniel, Blyth Daly, and singer Billie Holiday. Bankhead never publicly used the term “bisexual” to describe herself, preferring to use the term “ambisextrous” instead.

Bankhead appeared in nearly 300 film, stage, television, and radio roles. She also performed over a dozen plays in London in the 1920s, one of which was in 1924, when she played Amy in Sidney Howard’s They Knew What They Wanted. The show won the 1925 Pulitzer Prize.

She was not as public about her humanitarian efforts but supported foster children and helped families escape the Spanish Civil War and World War II.

Bankhead died in Manhattan on December 12, 1968, at age 66. from double pneumonia complicated by emphysema due to cigarette smoking and malnutrition. Her last coherent words reportedly were a garbled request for “codeine … bourbon”.