The Town of St Joseph is a central figure in the story of Childgrove. In Edward’s time, it was a busy, thriving city of commerce. Millionaires built giant gothic mansions from companies’ profits and engaged in civic displays with boulevards and parks. It had more miles of overhead streetcar lines than New York City, with a 26-mile-long parkway system, a huge amphitheater, a lakeside amusement park with a dance club that jutted out over the water, and numerous nationally known candy factories. The last surviving, the Chase Candy Company, is a fraction of the size at its peak, manufacturing just one of its inventions, the Cherry Mash. Its history is well known as the “jumping off point.” for Western settlers in the mid-1800s. This was as far as you could go by rail thanks to the Hannibal & St. Joseph R.R. It was also well served by its location on the Missouri River, and manufacturing and supply houses boomed for goods heading west. Jesse James met his end here, and just a week later, Oscar Wilde watched from his window at the World Hotel, where Jesse’s wife and children were staying as the contents of their home together were stripped for auction. Wild mused that America often made heroes out of murderers and thieves, but one might argue that Robin Hood and Dick Turpin were held in the same regard in his home country. Abraham Lincoln sat on the shores watching the steamboats, as did Mark Twain not many years after. It made sense that the Powell Brothers would locate their import warehouse here.

Edward’s home, the house I stood outside as a child, was torn down in the early 2,000s, and haven’t located a picture of it. Instead, I made it an amalgamation of several houses typical of St. Joseph. The Exterior is modeled on the R.T. Davis Mansion, known as the Aunt Jemima House. It was built in 1890 by the man who bought the Pearl Milling Company and made Aunt Jemima pancake mix a national brand. The company recently reverted to the original St. Joseph mill’s name in the rebrand.

Downtown, Milton Tootle built a nearly $200,000, almost 1,500-seat opera house, which opened on December 9, 1872. With its three balconies and massive, opulent boxes, architect W. Angelo Powell’s French Renaissance grandeur wowed audiences then.

Sarah Bernhardt, Buffalo Bill Cody, Edwin Booth, and Oscar Wilde were the performers on the giant stage, measuring 100′ wide, 67′ high, and 50′ deep. The Dubinsky Brothers took on the theatre as its fifth operator and would switch from Dubinksy live stock to motion pictures in 1919. Finally, in 1933, the building was completely gutted down to its four walls and became the Pioneer Building with offices and some retail. On November 21, 2016, the 144 year old theatre was gutted in an epic fire. The city called for its demolition within a month. With the theater and the bank long gone, the only remnant of this is one lonely lion that still sits on a country road where Saxon’s summer home used to sit.

So much of the history here has connections. Oscar Wilde is referenced in London with The Bright Young Things, having already passed years before, but he also had a link with St Joseph. When Oscar Wilde appeared at the Tootle Opera House, he apparently was not too enamored with local bank owner Able Saxton and wrote a poem about him. Edward mentions seeing a performance of the original production of Babes in Toyland, which opened on Broadway in 1903 and then toured the country for many years. The Tootle was one of those stops. The basic story is about orphans Alan and Jane, the wards of their wicked Uncle Barnaby, who wants to steal their fortune. It involved multiple attempted murders, demonically possessed dolls and forced marriage. Little wonder it gave Edward nightmares, which is the best explanation I have for why I find the theme song unlistenable even now.

Later, Edward visits the building when it has become a movie theater on the advice of “Murphy,” the newsboy. Years later, he befriends Stephen Tennent, whose mother’s cousin was Oscar Wilde’s last lover.

In high school, I volunteered to teach guitar to some of the residents of the “State Hospital.” Opening on November 9, 1874, the State Hospital for the Insane No.2, more commonly named the Lunatic Asylum #2, pledged the lofty goal of “the noble work of reviving hope in the human heart and dispelling the portentous clouds that penetrate the intellects of minds diseased.” For 127 years, it occupied the spot, and the town eventually grew around it and swallowed the farms that once made it an autonomous institution. One of those fields is where the shopping mall sits today. In 1899, it gained the name the St Joseph State Hospital, but the old name stuck around for much longer in the town vernacular. Patients were regularly led on walks to take fresh air and sunshine as part of their treatment, and many worked on the farms. By the early 1950s, the facility had grown to nearly 3,000 beds and housed everyone from the criminally insane to the mildly depressed. The workload was so severe that little was done for the patient besides maintenance. By the 70s, the population was dwindling. I was trapped there for a night during a blizzard and spent it locked in a padded cell where I could sleep safely. It was deathly quiet, yet filled with voices whispering from memory. Not long after that, with modern treatment and medications, the facility outlived its mission, or instead, it was fulfilled by other means. Today, it is a prison, and the tunnels are filled with tons of concrete. But the cemetery is still there, now on prison grounds and hence off limits, where crumbling stones bear only numbers. There are no surviving records as to who was buried under what number. These are truly lost souls. David was fiction, but the 2000 patents who remain beneath this sod, many abandoned by relatives, were not.

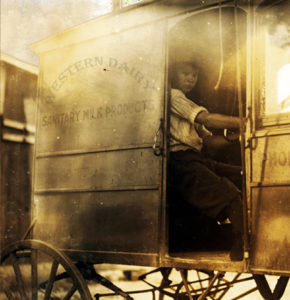

These images are presented to give you a glimpse of that world, the ghost of his time, echoing into mine. Do you see the scenes of Edward’s story in them?

St. Joseph in the 60s. The world I knew.

3107 Edmond St, St. Joseph, MO, was the first place I knew in this world. It was built in the early 1900s, with built-in cabinets and mirrors, pocket doors, and a stairway that branched off in several directions. It would have been considered upper middle-class compared to the city’s mansions, but it was a palace to me. My parents spent 15 years working on it, building an addition on the back, modernizing the power and plumbing, re-roofing, and a hundred other little things. Finally, just shy of my 10th birthday, they discovered the foundation needed significant work, which was more than they could handle. The people who bought it didn’t have the Elm tree sprayed, and it died the following year. It changed hands a few times, apparently ending up as a drug den. The church across the street bought it, and my parents begged them to let us gather mementos, but the new church owners were so spooked by the drug paraphernalia and damage that they refused and plowed it down intact, just like they did Mrs. Harrison’s house next door years before. The entire end of the block is now a parking lot.

About ten miles south of town was Bean Lake, where we had the cabin my father and grandfather had built together. We spent many weekends throughout the year and a week every summer there. When you had no air conditioning, getting out of town in July or August was a treat because it was often 10-20 degrees colder by the water. I flood took it and everything else recognizable from that end of the lake in the late 70s, and the oxbow lake has since dried up almost completely. It is now a state wildlife preserve.

Dad would drive us down U.S. 59 for about 18 miles as we paralleled the train tracks, me waving to the breakmen in a time when cabooses still existed. I could not have known who Carl Sandburg was back then, but he laid some of those very tracks, though not many, in the short time he worked as a gandy dancer on it. He did mention it in his journals.

“My Irish boss, Fay Connors, hired me at a dollar and twenty-five cents a day, and I was to pay him three dollars a week for board and room in his four-room, one-story house thirty feet from the railroad tracks at Bean Lake. I tamped ties several days from seven till noon, from one till six in the evening. On Sunday, I washed my shirt and socks. At the end of two weeks, on a Sunday morning, I hopped a freight for Kansas City and left Boss Connors to collect for my board and room out of my paycheck. The rest of the pay was still owed and was never collected. If Connors did get it, he couldn’t have sent it to me, as he didn’t know my address, and I wasn’t expecting to have any address for weeks or months.“

My world wasn’t big by anyone’s standards, but it all fit me just fine. When I wasn’t at school or home in the same neighborhood blocks from each other, I would be downtown at my father’s shop, both of which play a part in my portion of the story. The Goldsberry building, as it was referred to in the Historic Places register, was built in the mid-1840s and attached to the back end of the Missouri Valley Trust Company (featured in the movie “Paper Moon. I got to stand with Peter Bogdanovich and watch him film Tatum O’Neil). The upper floors were empty the entire time I knew it, and I could feel the emptiness. Yes, that sealed-up door in the basement was real, too, leading out to a cavity under the sidewalk that has since been filled in.

Just down the street was the Market Square. It was declared a historic district and placed into the National Register of Historic Places by the St. Joseph Historical Society on March 17, 1972, but the Urban Renewal Program had already slated it for demolition. The city claimed the large government grant for the “Cleanup” had already been received, so it was too late to stop. Preservationists were going to court to stop it, but the demolition crews arrived in the middle of the night on Sat. Dec 1, 1973, just days before the court date, started swinging the wrecking ball. The case became moot, and the land was redeveloped for a Holiday Inn, now sitting vacant. An incredible amount of history was destroyed, including the original Pony Express Freight Depot. Before they were done, the city had pulled down almost 150 classic and highly decorative buildings in the downtown area. There have been numerous attempts to revive it, but there are now blocks of empty buildings, and the area has become known for drug abuse and crime.

So, this was the world into which I was born, a product of the history before me, perhaps imbued by those ghosts of history who could feel them and all their hopes and dreams for the community that was slipping quickly away. I came into that world to hear, to see, and to contain the last bit of that dream before it was all gone. I was a child surrounded by others’ memories. I watched the parades go by from the stoop, watched the destruction of the buildings across from the big show windows, the imploding of the once opulent Rubidoux Hotel from the upper floor, and witnessed my father lock the door for the last time and walk away from 100 years as a St. Joseph business, another one left behind in the new world that replaced it. I felt the ghosts of this place stand with me every time.

If you Google St. Joseph now, the first result is that it was the birthplace of rapper Eminem. No offense to Mr. Mathers, but I somehow doubt he is at the top of St. Joseph’s pyramid. He, like I, are just the whispers in the quiet night.

Mrs Harrison, my next-door neighbor, gave me my first present the day I was born: my stuffed bear. I also have the Christmas stocking she supplied for my first Christmas a few months later. It’s been empty for a long time, but it still gets hung every holiday season in remembrance of her. These are two of the few tangible remains of that failed time, and like the crazy old man I have become, I remain what I was created for—the speaker for the dead.